When Two Towers wasn't enough

Necessity during Tim Duncan's rookie season led to the kind of lineup experimentation we'll likely never see again.

A very important thing people online may go back and forth about is what position Tim Duncan predominantly played, usually spurred by the equally urgent question of who the Greatest Power Forward of All Time is. If Duncan qualifies, the answer is almost unequivocally him. If the dissenting take wins out—after all, they may argue, Basketball Reference does say he played 63% of his minutes at center versus just 36% at the 4—then he boasts no such positional dominance, lumped in with the Kareems and Russells of NBA history. It’s a riveting, constructive debate and one that, in keeping with the themes and values of this niche newsletter, we’re forgoing to talk about the real story: that rogue 1%.

The idea of Duncan spending any time on the wing feels radical now, but it was touched on within his first moments as a Spur: at the 1997 NBA draft. This is Craig Sager speaking to him shortly after his selection:

“We’ve talked about you going out and even guarding some small forwards—can you do that?”

Duncan’s response: “I hope so. I think I have a lot of learning to do. I did a lot more this year, and I’m getting more comfortable with it. Hopefully I can go out there and learn along the way and get better at it.”

That this was even a talking point speaks both to the playing style of the late 90s and Duncan’s underrated fluidity coming into the league. While many today default to memories of him later in his career, simultaneously stationary and ubiquitous around the basket, he possessed the combination of craft and quickness as a rookie to get around any defender, an ideal complement and torchbearer for David Robinson.

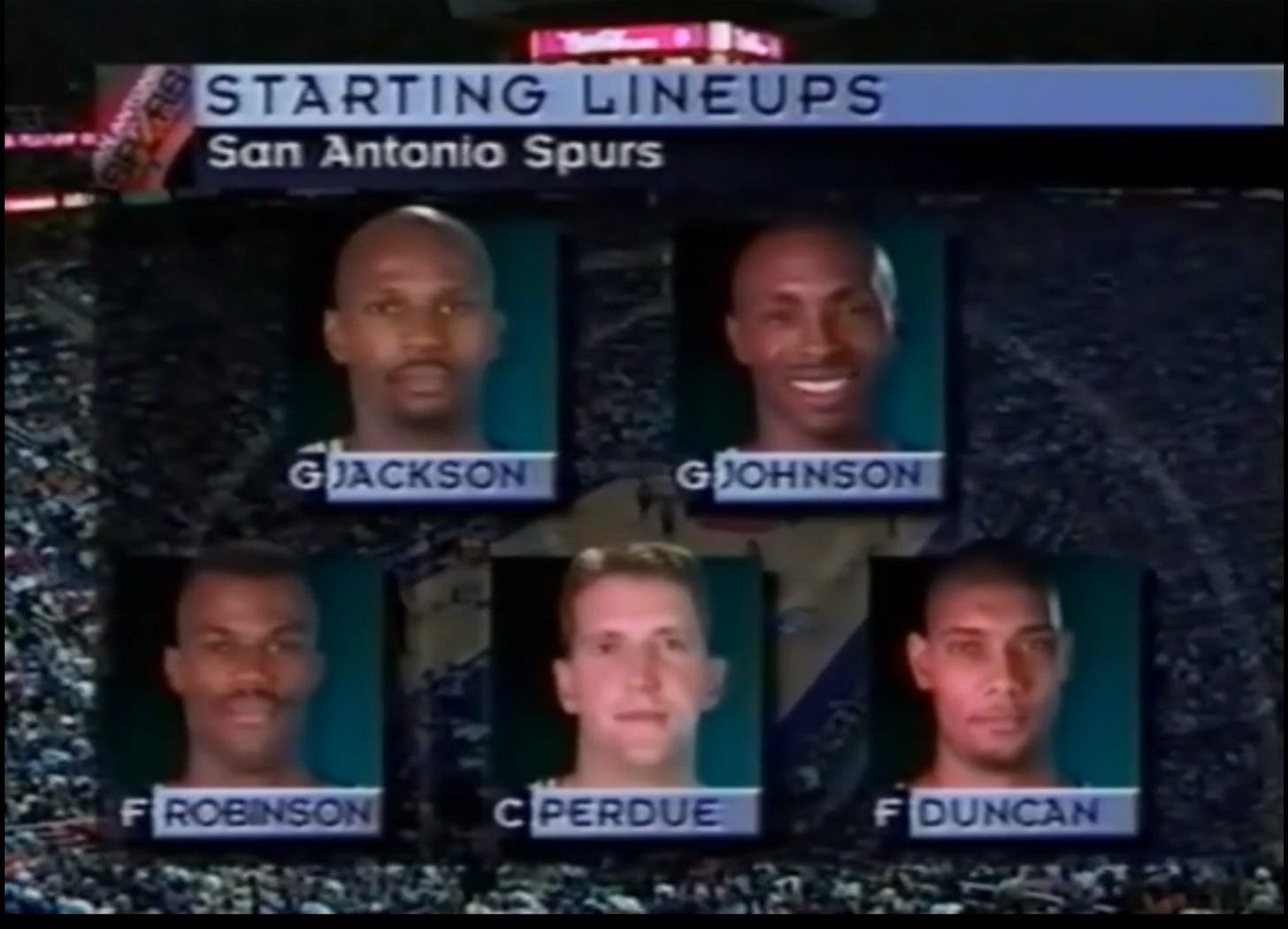

Still it was necessity that forced the Spurs’ hand in shifting Duncan down a position. On January 19th Sean Elliott played his last game of the season, felled by the same recurring quad injury that San Antonio would later diagnose Kawhi Leonard with. It left the Spurs relatively thin on the wing and deep with bigs. The next game, Gregg Popovich inserted center Will Perdue into the starting lineup to play alongside Duncan and Robinson, creating the “Triple Towers.”

“Pop kind of changed the offense a little bit, not significant, just a little bit,” said Perdue. “It was kind of one of those things tried on the fly ‘cus we’re losing guys to injury. Seeing who do we have left, let’s take the pieces we’ve got left and see what we can work out.”

Perdue notes it wasn’t always Duncan dropping down the 3:

“I was the only defined position—I played the 5. Tim and David kind of flip flopped back and forth together (between small and power forward), and their position kind of became more of matchup than defined position.”

Duncan and Robinson were both capable shooters from the midrange, but one of the first things to catch the modern eye about the lineup in the graphic above is the sheer lack of three-point threats. Duncan went 0 for 10 from deep that season, Robinson 1 for 4 and Perdue 0 for 1. Even point guard Avery Johnson seldom stretched the floor, hitting on just 2 of his 13 attempts in 2017-18. Only Jaren Jackson (37% on 3.6 attempts per game) posed any real threat.

And yet the change worked—the Spurs went 22-8 over the 30 regular season games that they rolled out the Triple Towers, including a win in Indiana where they held the Pacers to 55 points on 27% shooting from the field. It was the lowest point total at the time in the shot clock era, as Larry Bird (then a first-year coach with the Pacers) notes in his book, Bird Watching, when discussing his personal lows in coaching.

Duncan and Robinson’s ability to thrive outside their known roles says plenty about them as athletes, while their willingness to do so speaks volume about them as professionals.

“Because some guys would probably say no,” said Perdue. “They’d say, ‘Listen you’re not putting me in a position to succeed, I’m not doing that. You want me, a guy that should be playing in the post, in the mid post, to go out on the wing? That’s a recipe for failure, I’m not doing that. I’m calling my agent.’ I don’t think there was any hesitation whatsoever. I think they looked it as I can get out of the paint, I don’t have to bang with these guys, I can shoot jumpshots? I can do other things? Absolutely.”

Given Elliott’s injury and their success with the Triple Towers lineup, it made sense for Popovich to carry it over into the playoffs—not only Duncan’s first taste of the postseason but the first for him as well as a head coach. His defensive assignment: All-Star guard Jason Kidd.

Said Perdue:

“It was just one of those things where we get in the half court and thought, ‘Let’s put Tim on Jason Kidd. He can back off of him and then clog up the lanes and keep him from getting to the rim. Because we’ll let him continue to shoot jumpshots.’ It was one of those things where he’s still an NBA player but let’s try to see if he can beat us with the weakest part of his game. We know he can get to the rim, we know he can facilitate, let’s see if we can make him a shooter. How can we do that and take advantage of that. It’s not one of those things where this guy stinks—it’s just what matchup works best for us? What matchup can we throw out there where it exposes more of him than it exposes of us?”

You can watch the entire game on YouTube right now, which feels like tuning into a chess match halfway through, the board skewed in jarringly unique ways for each side. From the tip, Duncan chases Kidd around the perimeter, hanging back and generally daring him to take the outside shot. Instead of challenging, Kidd routinely seeks out screens that switch the smaller Johnson onto him. On the other end, Duncan and Robinson trade off on the low block while Perdue, as was his mandate as the third unsung big, remained active off ball with cuts and screens.

It would be convenient to say that the game was largely decided on Popovich’s gambit, but the Spurs slowly move away from the tactic as the game wears on, Duncan eventually falling back to a more convenient defensive assignment. Kidd puts up numbers (17 points, 11 assists and 6 steals) but only makes 7 of his 19 attempts while being a negative on the floor and, most importantly, the Spurs steal a vital game in Phoenix and eventually take the series.

Popovich would continue to start the Triple Towers for the rest of San Antonio’s 1998 playoff run but, as next year’s championship run would prove, the Spurs were indeed at their best with a healthy Elliott—and *only* two 7-footers on the floor.